By 1981, nearly all of the major studios had entered the home video business, although some reluctantly. Upon doing so, they envisioned home video sales much like music sales – where a record was normally purchased directly from a retailer. But in the video market, this wasn’t happening. As it turned out, the vast majority of the public couldn’t justify spending $50+ ( $150+ in 2019) on a single movie they may only watch once. What most wanted was simply a one night stand with the movie of their choice. Naturally, retailers adapted by renting titles intended for sale only. The business model was so simple to operate, that video rental shops began popping up in towns all across the country – supermarkets, gas stations, convenience stores and even the U-Haul truck rental service jumped on for the ride with their own video rental services.

Of course the studios weren’t happy, but it was too late – they couldn’t tame the beast. It drove them nuts not knowing how many times their films were being seen, especially with the rising popularity of home video. They had grown comfortable with the original model – each viewing resulted in a cut of the profits. Prior to home video, most viewings were public and therefore documented. Royalties or fees corresponded with that number of public viewings. But technology dramatically changed the industry’s landscape, causing executives to slowly lose sight of those numbers.

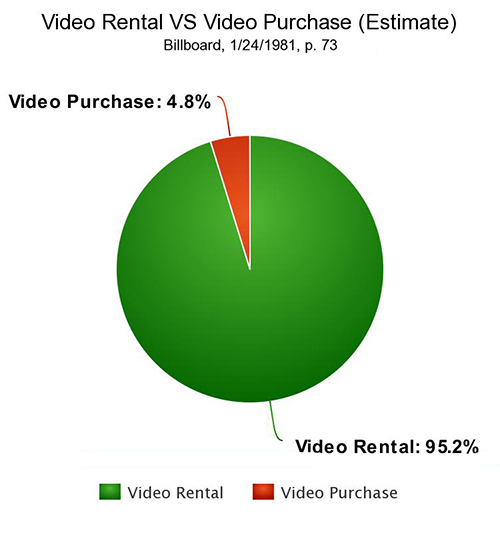

At the time, rentals outnumbered purchases 20 to 1. (8) The universal gut reaction to this rental trend was to add a surcharge or increase the retail price of their videocassettes. This allowed the studios to cut deeper into a particular title’s rental earnings. For instance, if the retail cost of a title was $79.99 (nearly $200 in 2018) and rentals cost $5.00 each, the video would need to be rented 16 times before the retailer broke even. For Paramount, this was a sufficient enough system (they’ve already been testing the market through Fotomat’s rental service). (6) According to Richard Childs, vice president of Paramount Home Video, “We aren’t sueing any dealers and we’re not going to. No one has to sign an agreement not to rent. We sell the product with a price that includes rental royalties and the dealer does what he wishes.” (8) As for the other studios, raising the price was only a temporary solution, as it was their only leverage at that point. From their paranoid perspective, that same videocassette could be rented 100 times at $5 a rental, netting the retailer a profit of $420, while they, the studio, only made approximately $10 on the sale of the cassette (after all other costs). Although this rarely ever happened, the mere possibility terrified studio executives nonetheless. According to Morton Fink, president of Warner Home Video at the time, the studio felt that they were “giving away their crown jewels” and were “not getting any part of the rental.” (1)

“This announcement serves as your notice that all existing dealer and wholesaler agreements are hereby cancelled.”

-Warner Home Video, in a letter to retailers announcing their new "rental only" program in 1981

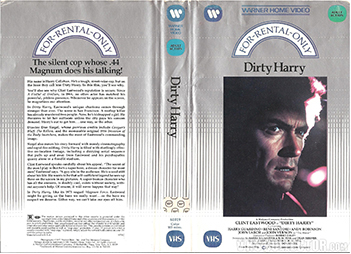

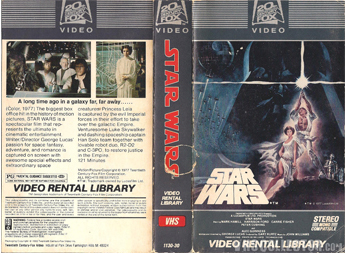

For a stint between 1981 and 1982, Warner Home Video, MGM/UA, 20th Century Fox, and Disney Home Video experimented with “Rental Only” releases for top titles. First through the Fotomat franchise, and then through their own home video divisions. The purpose was to give retailers incentives to sign a contract with the studio where rental earnings were more fairly split. Most of these programs involved a retailer leasing a particular rental-only cassette for a fee (usually a top title not available for sale), and after a designated period of time, they would then have the option to outright purchase the videocassette and rent it as often as they wish. According to Disney’s president of Telecommunications and Non-Theatrical Division at the time, Jim Jimirro, the intention was to support their “authorized dealers and give them a tremendous advantage over those who rent without authorization… Unauthorized dealers will never get Dumbo.” (4) Fink announced Warner’s own vision for a rental-only program at a press conference, where he stated, “we will no longer sell our products to anyone.” (2)

Because each studio had their own rental program, separate paperwork had to be filed for each one by the retail establishment. This was a clerical nightmare and the retailers were losing patience. Not to mention, Warner had issued a recall on all cassettes sold prior to the new rental-only program, meaning they had to be sent back to be repackaged as “rental-only” cassettes. Enough was enough. Content producers were also becoming annoyed. The rock band Queen quickly defected from Warner Home Video upon their announcement of the rental-program, stating that “We’re not going ahead with Warner Home Video [for their release of Queen’s Greatest Flix] and the sole reason is that we don’t agree with their marketing plan when it comes to music cassettes. We’re adamant that it makes absolutely no sense to rent a music cassette like this.” To which a spokeswoman on behalf of Warner replied, “The rental policy just went into effect. It’s really too soon to talk about changing it.” (3)

Examples of "Rental Only" packaging

Predicting the storm ahead, in December of 1981, videocassette distributor Noel Gimbel organized a meeting with 200 retailers from the Chicago area to explain the new renting programs the studios intended to enforce. According to Gimbel, when he asked the crowd how many would follow these new policies, only 30 of the 200 raised their hand. Needless to say, retailers were not happy. They felt as if they were being bullied into buying a videocassette twice – once for the permission to rent it to patrons and second, to buy it outright after a specified period of time. This ultimately meant they had to double the cost of a rental to receive any returns on it. They were also unhappy with having to take on large packages of videos rather than selecting particular ones that did especially well. But Gimbel and the retailers knew their rights under the First Sale Doctrine. They played along for a short while, but enough was enough. Not seeing a solution in the immediate future, Gimbel created The Video Software Dealers Association (VSDA) to represent video retailers. They would have their first official meeting the following month at a Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Frank Segers in Variety described the meeting: “In what appears to have been a spontaneous outpouring of pent-up hostility against recent rental programs, they declared the revolution had begun.” Shortly after, they would become a close affiliate of the National Association of Recording Merchandisers (NARM).

Needless to say, the rental-only programs lead to an incredible backlash. The biggest rental chains were now taking on fewer titles from the studios. Despite the outcry from retailers, the studios persisted. Disney Home Video took their rental-only program especially serious, going so far as to filing suit against two Video Station stores for trademark infringement. Since Disney lawyers couldn’t hit the stores for renting titles intended for sale (as they were protected by the First Sale Doctrine), they instead brought them to court for duplicating the packaging of their videocassettes (at the time it was a common practice to replace the original video packaging on the shelf with a duplicate, so that once the videocassette’s rentals ran its course, it could then be repackaged in the original packaging and sold as new). In the end, the cases were settled out of court, but the issue remained: how could the studios adapt to this rapidly evolving marketplace? Will they ever see eye to eye with retailers? By the end of 1982, many of the studios abandoned their failing rental programs. MGM/UA’s program only lasted seven months before they officially ended it due to a “lack of understanding and acceptance of the plan.” (7) It seemed like it was time for the studios to moved on to plan B – changing the law.

With the failure of the rental-only models, the MPAA, the strong arm of the Hollywood system, embarked on a crusade to amend the First Sale Doctrine, the law which allowed for the rental of videocassettes. Relishing the spotlight, Jack Valenti, president of the MPAA, often spoke directly to the media on behalf of the studios. Although he presented himself as a friend to retailers and trade organizations, he often had fierce debates with them in the press. When the vice president of the Electronic Industries Association (EIA), Jack Wayman, expressed his support for the First Sale Doctrine, Valenti struck back calling him “a stupid idiot.” Wayman responded by saying Valenti knew nothing of the home video market and that he was “just mouthing what Hollywood tells him.” (5) But this wouldn’t be the first time Valenti would exchange blows with Wayman or the EIA. It continued as the Universal v. Sony lawsuit played out - an old battle that was now being fought at the Supreme Court. It goes without saying that both sides had diametrically opposed viewpoints on the issue of home recording as well.

Of course, those who opposed the amendment pushed back. VSDA memberships continued to rise and several other video dealer associations emerged. The EIA formally joined in the VSDA’s fight to uphold the Fair Use Doctrine. With the success of the organization, the VSDA decided to organize their first dealers’ conference to discuss the issues affecting the market. Held in 1982, the event had keynote speakers from not only the top dealers and distributors, but also representatives from the home video divisions of Hollywood’s top studios. Although topics at the event included concerns involving standardized packaging and marketing advice, the elephant in the room couldn’t be ignored – the First Sale Doctrine debate. By the third or fourth conference, the issue had become such a sensitive topic that studio representatives refused to comment on it.

“The First Sale Doctrine... seriously undermines the incentive to create.”

- The Reagan Administration (1983)

At the onset, things looked good for the MPAA. The Reagan Administration even wrote a letter to Congress, expressing their support for an amendment to the First Sale Doctrine. In it, it states: “The First Sale Doctrine, as applied to copyrighted phonorecords and audio/visual works, seriously undermines the incentive to create.” The NEA also supported an amendment to the First Sale Doctrine, stating that it “works a substantial injustice to the nation’s creative community and, thereby, to the nation.” They went on to claim that record and video rentals have already negatively impacted the industry, adding that, “Such losses have substantially reduced the willingness and ability of record and film companies to release new works, sign new artists, experiment with unknown talent and pay for the less popular artistic forms – such as classical, jazz, ethnic and gospel music – that are traditionally subsidized by the occasional hit record or film.” In retrospect, its funny to think anyone would actually believe this when you consider the avalanche of content that was made as a result of videocassette rental. If anything, the new industry created a new marketplace for independent content creators to sell their work, regardless of its technical merits.

In 1984, the record industry won their own battle in Congress, resulting in the Record Rental Amendment of 1984. As an exception to the First Sale Doctrine, it restricted the renting of musical works to discourage home copying. Ultimately, it didn’t make much of a difference. Public libraries were still permitted to lend music out at no cost, not to mention the public preferred to purchase their music anyway. According to reports, there wasn’t much opposition to the bill, primarily because at the time, the country only had approximately 250 record rental stores. Home video on the other hand had a lot more at stake. With over 10,000 rental stores already in operation across the country, there were many with deep pockets willing to defend the doctrine. In January 1985, the VSDA held a meeting specifically on the First Sale Doctrine issue to further discuss how they can end the battle once and for all. The DC chapter of the organization promised to be the most vigorous, lobbying hard on behalf of video retailers and distributors.

Hoping to ride the coattails of Record Rental Amendment of 1984, the studios continued with their agenda, but by the beginning of 1985, it was too late. Videocassette rental had already saturated the market and Americans were hooked. There was a video rental shop in nearly every town across the country and the year prior saw the sale of nearly 8 million VCRs, with tens of thousands of videocassettes titles already on the market. VCRs were suddenly the cover stories of magazines like TIME and Newsweek, with various specialty magazines dedicated to the bustling marketplace circulating on newsstands everywhere. Home video had become a staple in American culture and there was no turning back. The home video revolution was in full swing and not even Congress could stop it. Universal Pictures had already lost their fight against Sony’s VCR in early 1984 (again) and Congress began backing away from the First Sale Doctrine issue. I’d like to think that perhaps many these Congressmen were finally reaping the benefits of having their own video cassette recorder. On a legislative panel at a CES event in 1985, Representative Michael DeWine told attendees, “My prediction is Congress will not take any action at all. I think that issue is dead this year. I think it’s going nowhere.” As one would expect, the audience exploded in applause. He went on stating, “It’s not really a high priority item with voters today.” At their own event held in the August of that year, VSDA executive vice president Mickey Granberg stated, “For one thing, the first sale (controversy) is, well, I don’t want to say it’s over, but it’s very, very far back on the back burner… it’s not that much of an active issue.”

When it became clear to the studios that they had lost yet another home video battle, their only recourse was to continue dropping videocassette prices to widen the sell-through market and discourage piracy. This would ultimately make everyone somewhat happy - the public and rental shops were now purchasing their videos for a more reasonable price, while the studios were getting a huge boost in home video sales. Although the VSDA and retailers won their battle to uphold the First Sale Doctrine, there was still yet another conflict to confront. Where once discussing adult videocassettes was an embarrassment the VSDA avoided, they were now front and center. They made them the focus of their next project - confronting the obscenity laws that were taking down video stores across the country.

References:

-

Fast Forward, Lardner p. 189

-

Fast Forward, Lardner p. 194

-

Billboard, Douglas E. Hall, 10/31/1981 - p. 114

-

Variety, 07/15/1981, p. 42

-

Variety, Tony Seidman, 08/31/1983, p. 34

-

Variety, 10/29/1980, p. 53

-

Billboard, Laura Foti, 09/4/1982, p. 3

-

Billboard, 1/24/1981, p. 73

Comments 3

Login / Register to post comments