"I thought maybe what I can do is acquire the rights to a bunch of weird and successful independent movies of that time and start my own label. I'll be the second one."

- Charles Band (2013)

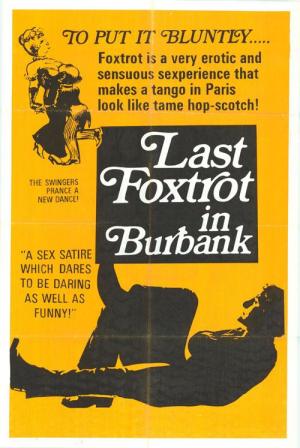

Of all the home video pioneers, Charles Band is probably the best known. But not because of his contributions to that specific industry, but rather his long legacy in producing cult cinema - a legacy that he continues today. At the time of this writing, he’s credited with producing over 280 films, and directing over 50. Having been born into a family already established in the entertainment industry, he was already on a path towards success. His father before him had already produced 10 movies when he himself decided to make his own in 1973 - an erotic parody called The Last Foxtrot in Burbank.

Four years later, Charles Band would make another erotic parody, this one simply called Cinderella (1977). The film was a hit and led to the productions of several other films, including End of the World (1977), Laserblast (1978) and Fairy Tales (1978). This success also allowed Band to experiment a bit - particularly in the emerging home video market. It all began in 1977, when he read an article about how tape duplicator Andre Blay licensed 50 films from 20th Century Fox for home video distribution. Although forms of pre-recorded home video existed before both Blay and Band, such as Castle’s 8mm films or the failed Cartrivision system, the Sony Betamax machine breathed new life into home video entertainment with its efficiency, recording capability and cost. Upon its release in 1975, the new device was adopted almost immediately by film enthusiasts, with many of them trading and selling recorded content even before Andre Blay made his deal with 20th Century Fox.

Upon reading the Andre Blay article, Band saw an opportunity of his own - a video label specializing in independent cult cinema and special interests. In a 2013 YouTube video, he recalls thinking at the time, "...maybe what I can do is acquire the rights to a bunch of weird and successful independent movies of that time and start my own label. I'll be the second label out there." [2] Having already established himself in the industry as a producer/director, he had all the necessary contacts to begin acquiring films. Whereas Blay, the Nostalgia Merchant, and Allied Artists focused primarily on studio films, Band takes credit for being the first to bring independent cinema to the newly emerging home video market. Ultimately, he created some of the most iconic video labels of the era, including Media Home Entertainment and Wizard Video. It’s for these reasons, I consider him a pioneer of the home video industry.

As we delve into Band’s home video timeline in more detail, bear in mind that this is not a complete timeline of his career in the movie industry, but only his foray into home video. As much as I would have loved to discuss all the lawsuits filed against Band, I only included ones related to home video distribution, however remotely. I should also mention that all of the information I’ve been able to gather comes directly from the trade magazines and newspapers of the era. I’ve made every attempt to be as accurate as possible. Now on with the show!

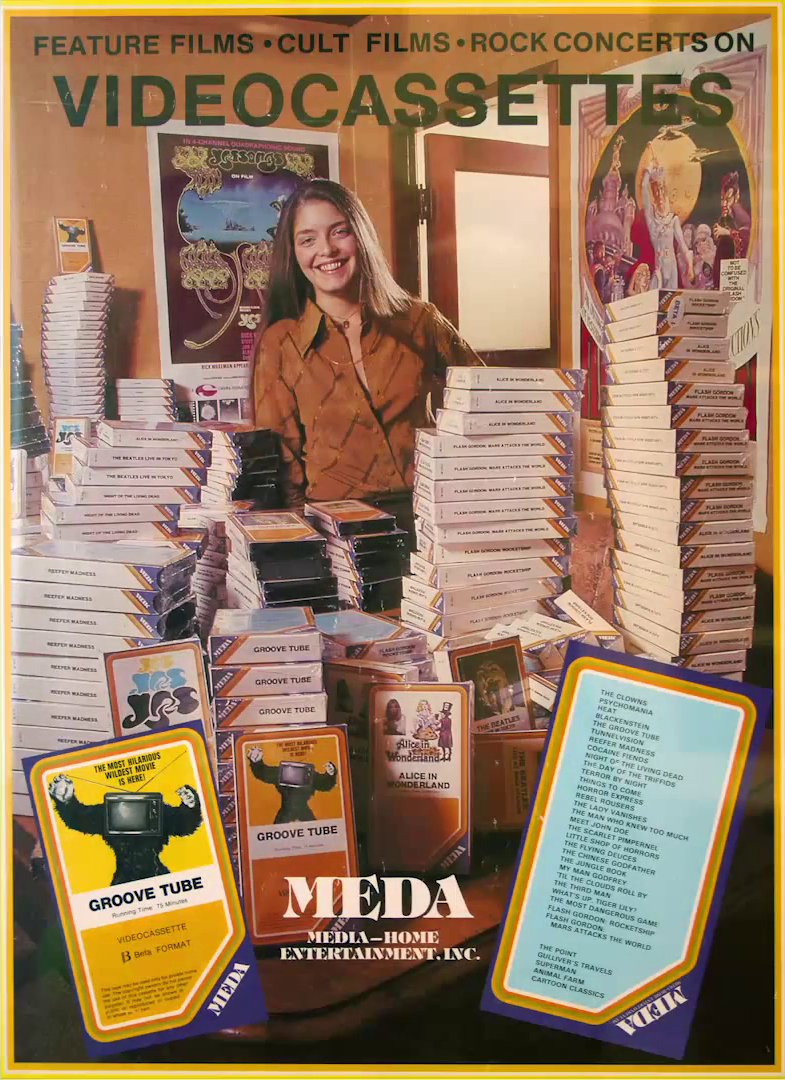

In February of 1978, Band announces the launch of M.E.D.A. - an acronym that stands for Media-Home Entertainment and Distribution Association. It also happens to spell out Band’s first wife’s name, Meda. [1] [2] In the following month, the company announces their first two titles: Flesh Gordon (1974) and Alice in Wonderland (1976). Over the following year, the young company builds their eclectic library when suddenly, they’re forced to learn a valuable lesson in home video distribution. In January of 1979, Abkco Music files a copyright infringement suit against M.E.D.A., claiming a videocassette entitled The Rolling Stones in Concert included music that wasn’t licensed. The judge issues a writ of seizure order for all masters and videocassette copies. [4] This marks the very first time where a music company sought legal action on a home video distributor. Not allowing the legal hurdle to curb their success, the year-old company has four of their releases chart on Billboard’s very first Top 40 Videocassettes list in November of 1979. The highest grossing of these being The Groove Tube (1974) at number 13. [3]

As M.E.D.A.’s business continued to skyrocket over the next two years, Band brings in three other partners in a move he would later regret. The business relationship quickly sours [2] and at some point between 1979 and 1980, he steps down as the company’s president and is replaced by fellow partner Ron Safinick. [5] Also during this time, the M.E.D.A. acronym is dropped from all print material and the company name simply becomes Media Home Entertainment (MHE) and is given a brand new logo. In March of 1980, MHE is sued by another music company, this time by Beatles' music publisher, Northern Songs. Again, its for copyright infringement, similar to their Rolling Stones dilemma. They settle out of court to pay approximately $26,000 in 13 installments.

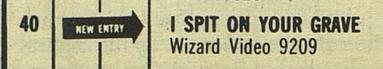

Unhappy with with his partners and perhaps the fact that he was losing control of the company, Band creates another distribution label in 1981 called Wizard Video. [2] Much like MHE, Wizard Video also focused on independent films and special interests, with a particular interest in horror and exploitation. In August of 1981, the new company has their first charting videocassette with the release of the exploitation film, I Spit On Your Grave (1976). It peaks at 24, spending 14 weeks in the top 40. [6] In an interview with Billboard magazine at the time, when asked about the success of I Spit On Your Grave, Band says “With most titles, it’s completely due to how hard we push.” He goes on to attribute its high sales numbers to its packaging, pricing and promotional support. [7]

In February 1982, Band strikes a distribution deal with Family Home Entertainment, a growing company that made its name by distributing children’s content (ironically, FHE would print their name on the covers of some of the hardest Wizard Video titles). The deal gives the company full control over domestic operations of the Wizard Video brand. According to FHE in an article by Variety, “Wizard president Charles Band has left domestic home video to concentrate on indie production.” [8] The irony of this is that just mere months of striking the FHE deal, Band creates yet two more home video labels - Cult Video and Force Video. [9] [10] Whereas the early Wizard line had a strange mix of cult, music, and comedies, these new labels focused solely on sleazy cult films. Such titles include Snuff (1975), Blood Feast (1963), and Famous T & A (1982). In May of that year, Billboard reports that George Atkinson, video rental pioneer, “has negotiated with Charles Band...to manufacture and distribute approximately 30 films.” [37] As much as I’d love to believe these two trailblazers worked together, I couldn’t find another link between the two. It's likely the deal fell through. In the end, both Cult and Force Video release nearly 20 films before being abandoned a year later.

As an interesting side note, Force Video unlike Cult Video, had a unique marketing approach. According to an article in Variety, Force Video president Jeffrey Abrams thought that “(advance Filmgore [1983]) orders are being boosted by the high-impact packaging and unique marketing that he’s trying to pioneer with Force Video. For example, retailers handling Filmgore will be given air-sickness bags to hand out to those who rent the tape, and certificates guaranteeing that the first viewer to die of fright or shock while watching the tape will be buried at Force Video’s expense.” [10]

"Any horror title that's been successful in the theaters will do well in home video."

- Charles Band (1982)

In the same month the FHE deal is struck, Wizard Video’s New Line Cinema title, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), debuts on the top 40 chart at number 23. It peaks at 6, spending 25 weeks on the charts. [11] In an interview with Billboard in 1982, Band explains that “a title like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a real breakthrough title. There's a built-in audience for that film.” [7] At its peak, it sells over 10,000 copies a week. An FHE spokeswoman comments on the success of the release, stating she hoped it wasn’t “a comment on society.” [12] This would be the last of the label’s titles to make Billboard’s top 40 list.

Sometime between 1983 and 1985, Wizard Video’s distribution contract with FHE ends, and Spectrum Video takes up the reigns. [13] In 1984, the company begins packaging their videocassettes in the now iconic “big box.” It debuts with the Italian title, Escape (1980). [14] Although Band claims to have been the first to use these boxes outside the adult video market, FHE were using them as far back as 1981. [2] [15] In fact, it may have been FHE who introduced the oversized packaging to the Wizard catalog before their departure.

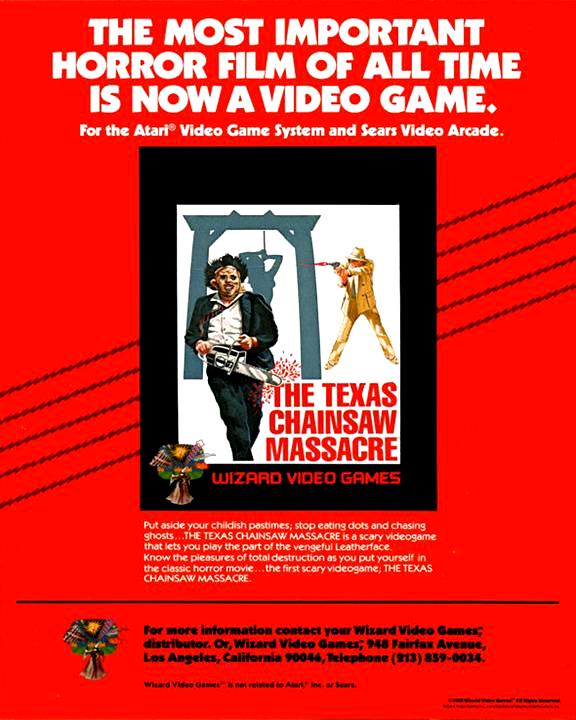

As he did entering the home video market, Band gambles yet again with another media platform. In March 1983, he announces a line of horror video games from his newly created Wizard Video Games brand. Because these games are inspired by popular horror movies, he believes the name recognition will include a built-in customer base [16]. For the Atari 2600, he releases Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Because few stores were willing to carry the controversial games, they sold poorly. This forced Band to abandon the development of the label’s next two games - one based on the film Flesh Gordon, and the other on the 80s new-wave band DEVO. [17] As an interesting side note, Variety, in covering the release of the two horror games, reports that Band “predicts a greater market for film-based video games presented on videodisc, since that technology will allow the games to be played with footage of the actual films.” He believes this so strongly, that he plans to shoot additional footage for his next film Metalstorm (1983) intended solely for a future video game version of the movie. [16]

In March of 1983, Band strikes a deal with Vestron Video to release select titles from the Wizard Video library onto videodiscs. Among these are Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979) and I Spit On Your Grave (1976). This marks the first time that these horror exploitation films are released to disc. [18]

Later that year in November, New Line Cinema sues Wizard Video for over $250,000 in outstanding debt. Commenting on the lawsuit, Band complains to Variety, stating that the original contract was “a bad deal from the beginning” and that “small independents don’t have a chance anymore.” He goes on to suggest that the earnings from the New Line films did not justify paying off the debts. This is interesting, since their biggest hit, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), is among those New Line titles. [19] This wouldn’t be the first time Band was accused of withholding payment from licensors. In later years, Meir Zarchi, director of I Spit On Your Grave (1976) revealed that he too was ripped off by Band. [20]

In December 1983, MHE sells for a whopping 10 million dollars to British company, Heron International. Although two of Band’s original partners remain with the company, Band takes his cut and jumps ship. [21] This couldn’t have come at a better time, as Band had that New Line debt to pay off. Four months following the filing of the New Line Cinema suit, Wizard Video is sued yet again. This time, by the MPAA for using an “R-Rated” logo on an unrated release of I Spit On Your Grave (1976). Jack Valenti, head of the organization, comments on the case, stating that “we will take whatever steps are necessary to deter those who would misuse the rating system and thus mislead parents who have come to depend upon it as a means of helping to determine what motion pictures their children should or should not see.” The MPAA demands that all proceeds from the sale of the videocassette be paid to them for having damaged the reputation of their rating system. [22]

Later that year in December 1984, Band is sued a fifth time (as far as this article is concerned) by Hemdale Film Corp. for misrepresentation. According to the compliant, Band told Hemdale, an investor in the film Ghoulies (1984), that there were no plans to renegotiate a distribution deal with Vestron Video. Based on this, Hemdale sells their interest in the film to Band, who later renegotiates a deal with Vestron anyway. This results in Hemdale being cut from the Ghoulies proceeds earned through the renegotiated Vestron deal. Hemdale seeks $1,700,000 in actual damages and $10,000,000 in punitive damages. [23]

In May 1985, Band revives Force Video and spends two million dollars licensing 60 films from mainly European companies. The concept behind the renewed label is to release the films in thematic packages, the first of which is called “Heroes, Pirates, and Warriors.” He inks a four year agreement for the label’s distribution through Vestron’s subsidiary, Lightning Video. [24] The following year, Lightning would also take on the Wizard Video catalog. [25]

In 1986 Band takes a tremendous leap forward with his production company, Empire Entertainment (also known as Empire Pictures), by turning it into a full-fledged movie studio. [26] As a result, he spends more time on producing films, and less on his home video ventures. Wizard, Force and Cult Video, all seem to dissolve by the end of 1987. In that year, Wizard Video releases their final three titles - Psychos In Love (1987), Mutant Hunt (1987) and Robot Holocaust (1986). They’re released in slipcase packaging, a step down from the vibrant oversized display boxes of their predecessors. [14]

"This group brought me a tremendous offer I couldn’t refuse."

-Charles Band on giving up Empire Entertainment in 1988

In March 1988, Band is sued yet again for misrepresentation, this time by Harkham Industries - a stakeholder in the film Swordkill (1984) (later called Ghost Warrior). They allege Band lied during contract negotiations when he claimed Vestron Video had put down a $1,000,000 advance when in fact, it was only $425,000. Harkham seeks damages in excess of $600,000. [27] Another lawsuit quickly follows from two finance companies alleging that Band failed to make payments on loans totaling over $1,000,000. [28] In total over the course of 5 years, Empire Entertainment accrues nearly $50,000,000 in debt and quickly begins to deteriorate. It is soon bought out by Eduard Sarlui, head of Trans World Entertainment, who absorbs the company through his newly created one, Epic Pictures. [29] According to Band, “This group brought me a tremendous offer I couldn’t refuse. As much as I love Empire and the projects I will leave behind, the opportunity to start again on a much smaller scale while getting to make movies again is just too alluring to pass up.” [30]

Rebounding from his previous studio’s collapse, Band creates another later that year, which he calls Full Moon Productions (later called Full Moon Entertainment). [31] During the company’s first 7 years, their films are mainly direct to video and distributed through Paramount Home Video. [32] In 1995, Full Moon Entertainment begins distributing their films themselves. In doing so, Band creates various home video sub-labels, such as Alchemy Entertainment, Surrender Cinema, Pulp Fantasy, and Pulsepounders. He even revives two labels from the early 80’s - Cult Video and Wizard Video (although changes its name to Wizard Entertainment for legal reasons). In a legal document filed with the state of California in June 2012, Wizard Video is merged into Epic Pictures, which is now owned by MGM. [33] This shows that Band lost Wizard Video the day he sold Empire Entertainment.

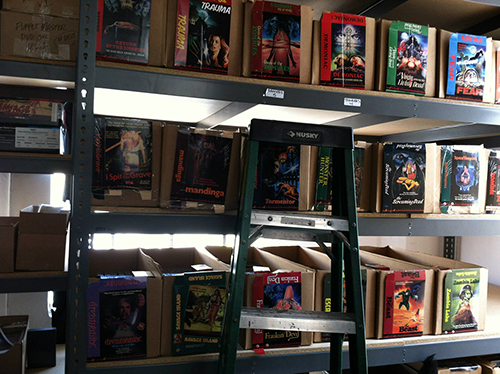

The following year, Band announces a discovery of new old stock of classic Wizard Video big boxes via a press release. In it, it states, “Horror legend and home video pioneer Charles Band had been putting off his warehouse cleaning for years. But during a recent overhaul of his extensive collection of collectibles, he unwittingly resurrected a veritable treasure trove of vintage horror limited-edition VHS boxes coveted by horror fans and serious collectors. Starting February 12th, fans will be able to purchase these original boxes with authentically duplicated VHS copies inside - at an incredibly reasonable price.” [34] As it turned out, the reasonable price was a whopping $45 each with $10 shipping.

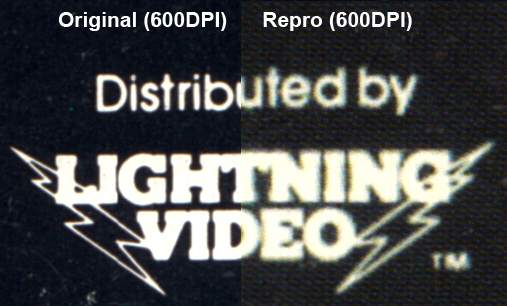

A view from within Band's warehouse and a comparison between the printing of an original box and Band's reprint

Although Band had his loyal supporters, much of the VHS collecting community found the press release very suspect. When I personally purchased one of these cassettes for closer examination, I proved conclusively through a YouTube video and a VHSCollector.com article that the boxes were in fact modern reprints and not original stock from the 80s. [35] When Band is asked to respond to the allegation by a Fangoria magazine editor, he doubles down on his original statement that they are in fact originals. [36] As a likely result of the YouTube video and article, sales of the reprints begin to plummet, and Band eventually abandons the project altogether, claiming conveniently that the remaining titles that were scheduled to be released were ruined in a flood (the poor sales likely didn't justify the printing costs of the later releases). The irony of all this is that because Band no longer owns Wizard Video, he may very well have been committing trademark infringement, using the “found in a warehouse” line as a loophole for their sale. It is a possibility that he could’ve licensed the Wizard Video trademark from MGM, but if you’ve learned anything from this article, you know how dubious this is.

There it is folks, the story of Charles Band and his adventures in the wild world of home video. Today, Band is still releasing his own films to home video and even his own streaming platform. Regardless of what we think of his questionable business practices or the quality of his films, he’s no doubt a B-movie legend, and pioneer of the home video industry.

Cited Sources:

(1) M.E.D.A. Offers Tapes for Home

Back Stage; Feb 10, 1978; pg. 11

(2) Charles Band's History of Wizard Video Collection on VHS

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsH_-XuPjlg

Published on Feb 7, 2013

(3) Tape/Audio/Video: Videocassette Top 40

Billboard; Nov 17, 1979; pg. 64

(4) Court Impounds Vidcassette Of Stones

Billboard; Jan 27, 1979; pg. 3, 81.

(5) L.A. Co. Creates Artist Promo Vidtapes For Home Use

Billboard; Feb 16, 1980; pg. 3

(6) Videocassette Top 40

Billboard; Oct 31, 1981; pg. 44

(7) Chart Reflects Indies' Success

Billboard; Mar 27, 1982; pg. 75

(8) Revamp FHE-Wizard Operational Linkup

Variety; Aug 25, 1982; pg. 52.

(9) Firm Deals Only In Cult Vidcassettes

Billboard; Mar 20, 1982; pg. 46

(10) Big Initial Orders On Force 'Filmgore' Splatter Pic Tape

Variety; Mar 9, 1983; pg. 122

(11) Videocassette Top 40

Billboard; Jul 24, 1982; pg. 31

(12) 'Chainsaw' Sells 10.000 A Week

Billboard; Feb 13, 1982; pg. 40

(13) Wizard To Lightning

Variety; Jan 22, 1986; pg. 72

(14) Wizard Video Library

http://vhscollector.com/distributor-gallery/69

Retrieved Jul 1, 2018

(15) Family Home Entertainment's release of "The Child"

http://vhscollector.com/movie/child

Retrieved Jul 1, 2018

(16) Vidgames Get Gore Galore

Variety; Jan 26, 1983; pg. 38

(17) Video-game Companies Re-evaluate Strategies

Arizona Republic; Sep 9, 1983; pg. F5

(18) Wizard, Vestron Sign Disk Distribution Pact

Billboard; May 14, 1983; pg. 53

(19) New Line And Wizard Video Settle Long-Standing Debt Fight

Variety; Nov 23, 1983; pg. 26, 28

(20) Meir Zarchi Interview on "I Spit On Your Grave" Blu-ray

Starz/Anchor Bay; Feb 8, 2011

(21) Heron Confirms Buy Of Media Home Ent. For Over $10-Mil

Variety; Dec 14, 1983; pg. 31

(22) MPAA Sues Over Mating Tag On XEquivalent Release Version

Variety; Feb 1, 1984; pg. 3, 126

(23) Hemdale Charges Band With Misrepresentation

Variety; Dec 26, 1984; pg. 4

(24) Empire Ent. Bows Second Video Label; Vestron Distributes

Variety; May 8, 1985; pg. 127

(25) Wizard To Lightning

Variety; Jan 22, 1986; pg. 72

(26) Charles Band's Empire Is Growing

The Film Journal; Mar 1, 1986; pg. 7

(27) Empire, Charles Band Sued Over 'Swordkill'

Variety; Mar 23, 1988; pg. 17

(28) Empire Sued By Two Finance Partnerships

Variety; Mar 9, 1988; pg. 6

(29) Empire Creditors Offered Settlement

Variety; Jul 13, 1988; pg. 8

(30) European Group Buys Empire From Band

Variety; May 18, 1988; pg. 3

(31) Full moon rises for Charles Band

Screen International; Oct 29, 1988; pg. 2

(32) Paramount To Distribute Band's Horror Classics

Billboard; Nov 5, 1988; pg. 55

(33) Wizard Video and Epic Pictures Merger Document

https://businesssearch.sos.ca.gov/Document/RetrievePDF?Id=01035536-15132780

Filed Jun 06, 2012

(34) Wizard Video Discovery Press Release

http://wizardvideocollection.com/press-release.html

Published: Feb 7, 2013. Retrieved: Jul 1, 2018

(35) Wizard Video VHS Re-releases: NOT ORIGINAL

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC6Dc1QMK1w

Published: Apr 8, 2013. Retrieved: Jul 1, 2018

(36) Wizard Video VHS Re-releases: NOT ORIGINAL (Part 2, Follow Up)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95umkdPtrpE&t=1s

Published: Apr 10, 2013. Retrieved: Jul 1, 2018

(37) Atkinson Firm To Go Public, License Films

Billboard; May 1, 1982; pg. 42

Comments 0

Login / Register to post comments