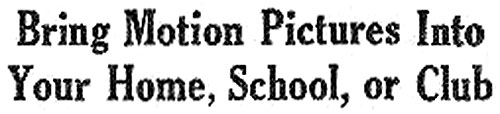

In 1910 across the Atlantic, Pathe Freres of France began development on a home projector using a new stock - 28mm safety film. It was released in the later part of 1911, making it the first projector and format combination intended solely for home entertainment. The Pathe Kok projector included a wooden carrying case, a projection screen and a catalog which initially offered 48 printed films. Perhaps having been stirred by this development overseas, Edison raced to the market with his own domestic projector, the Home Kinetoscope, in early 1912. It was first demonstrated in New York on March 27th of that year, where it was described as “...simply a miniature moving picture machine, a biograph that a child can handle, and that an ordinary living room can hold.” Made specifically for home entertainment, it’s more compact and safer than its predecessor, the Projecting Kinetoscope (using 22mm safety film as opposed to 35’s inflammable nitrate stock). This new gauge, exclusive to the Home Kinetoscope, remains a unique oddity to this day, as it used three columns of 6mm frames to triple the amount of content that could fit onto each reel. As with previous devices, catalogs were available to purchase additional printed films (mainly educational content). Despite being among the very first motion picture projectors made specifically for the home, the device was a commercial failure.

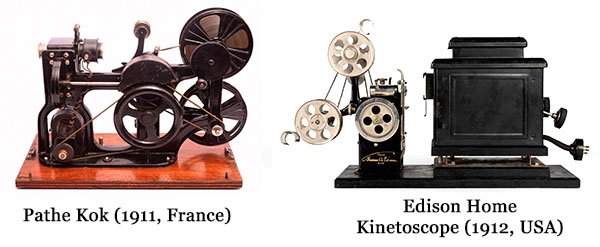

Things fare better for Pathe Freres, whose Kok projector and 28mm format outlives that of Edison’s. The success of the device inspired entrepreneur Willard Cook to set up the Pathescope Company of America (which basically functioned as a franchise), through which he imported and sold the Kok to the American public for the first time. He immediately began marketing it with demonstrations on luxury liners and in department stores, initially targeting those who could afford the pricey machine. In 1916, Cook ups the ante by developing a new and improved projector for the American market. Called the The New Premier Pathescope, this upgraded model is marketed as being "so exquisitely built that its large, brilliant, flickerless pictures amaze expert critics." But most importantly, the new machine is more compact, weighing only 23 pounds and "can be carried in a small suit-case." This smaller form reduced production costs, making it slightly more affordable.

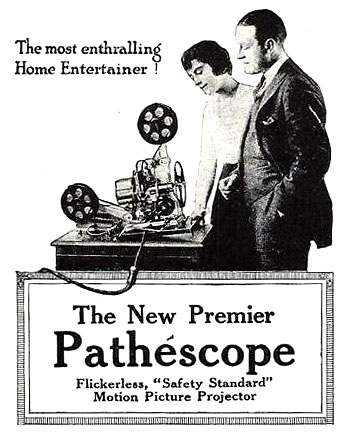

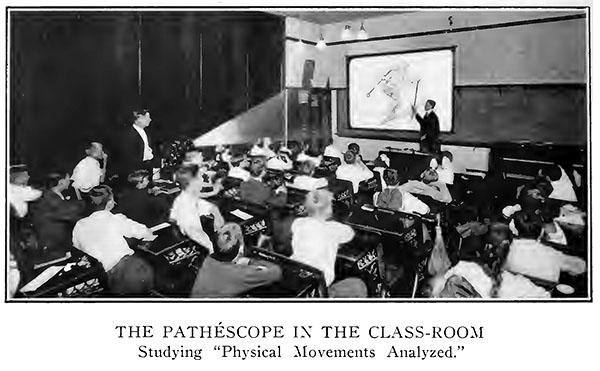

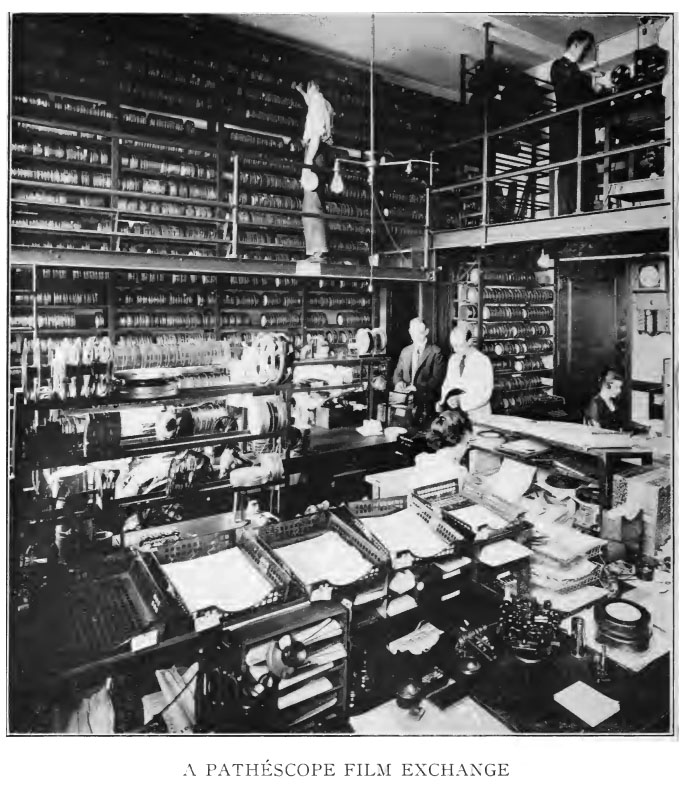

As demand grew for printed 28mm films, so did the PCA’s extensive library. They provided over 1000 different subjects by 1920, any of which could be rented through their mail-order catalogs. These films included an array of topics and genres, including comedies, travelogues, cartoons and westerns. Believing they could profit most from the educational sector, in 1919, they published a pamphlet entitled, Education by Visualization: The Royal Road to Learning Lies Along the Film Highway. In it, they argue that children are visual learners and as such, every classroom would be incomplete without a Pathescope projector. One paragraph reads:

“No matter how many times you may have read your Shakespeare, Stevenson, Eliot or Poe, have you not sat in a motion picture theatre watching closely, with the greatest interest, the preproductions on the screen in motion pictures of “Macbeth,” “Treasure Island,” “Adam Bede,” or “The Raven”? It is only natural then that the motion picture should be brought into the classroom to teach almost every subject and that the greatest educators and the greatest educational organizations in America should endorse the motion pictures, because with it the interest is already created.”

Although 28mm safety film was growing in popularity, there were still many non-theatrical locations (such as schools, lodges, churches, and even homes) that were using flammable 35mm film. Because of this, concern began to mount, as these smaller venues had neither the fire booths nor the insurance that large theaters were required to have. In 1918, Alexander Victor, a projector manufacturer from Davenport, Iowa, argued before the Society for Motion Picture Engineers that the 28mm safety gauge ought to be made the standard for all non-theatrical use. Unable to argue against safety, the SMPE agreed. Cook reluctantly concedes to Victor’s points, offering to lend his “cooperation in every way possible to those interested in the adoption of the new standard.” In reality, this was just a way for Victor to get a foothold in the 28mm market without fearing a possible lawsuit from Cook. Once everything was settled, it wasn't long before Victor and several other small projector makers jumped into the 28mm business. However, this new standard wouldn’t last very long, as five years later, even smaller gauges were introduced.

But meanwhile, as 28mm still reigned as the preferred non-theatrical format, an unusual attempt is made at home movie exhibition. First marketed and sold in 1921, Charles Urban’s Spirograph used large discs to store the motion picture. But rather than using grooves like the phonograph record that inspired it, each disc arranged the frames of a film in a spiral. As the disc spun in the device, its operator could look into an eyepiece to view the moving picture. During this period, projection technology for the home was already on the rise, causing similar peephole-type devices (such as the Kinora) to fall by the wayside. This begs the question, why would Urban back an already outdated concept? Suffice it to say, the Spirograph was only available for two years before being forgotten. It is believed only 200 were ever made. Although the device had virtually no impact on home video history, it's remains an interesting curiosity nonetheless.

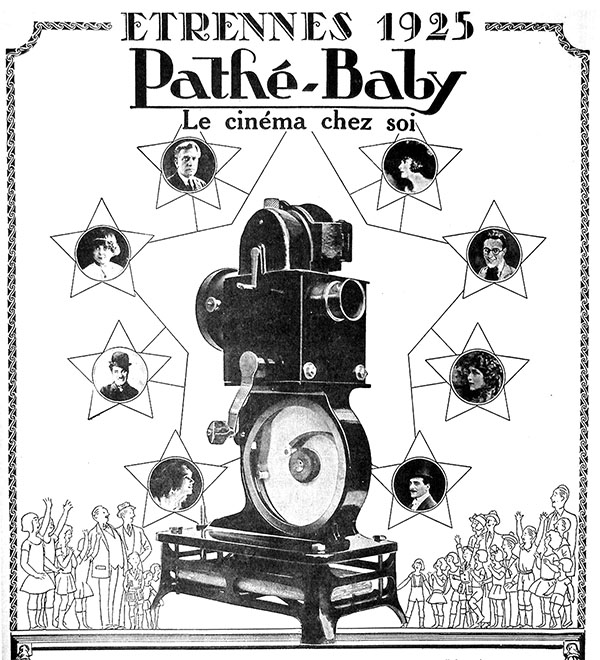

In 1922, Pathe introduced a dramatically smaller film format, 9.5 mm, intended for viewing commercial movies in the home. It was created for the new Pathe Baby line of products, which included a small projector and shortly thereafter, a camera for amateur cinematographers. The smaller film gauge meant an even lower cost to consumers, and as such, its popularity spread throughout Europe. The new format and its projector quickly replaced the magic lanterns that were popular in the homes of the French upper-middle class. In the United Kingdom, the format is especially successful, having been embraced by film collectors. Despite this, it never picks up momentum in the U.S., likely due to Kodak’s influence and the new format they would launch the following year.

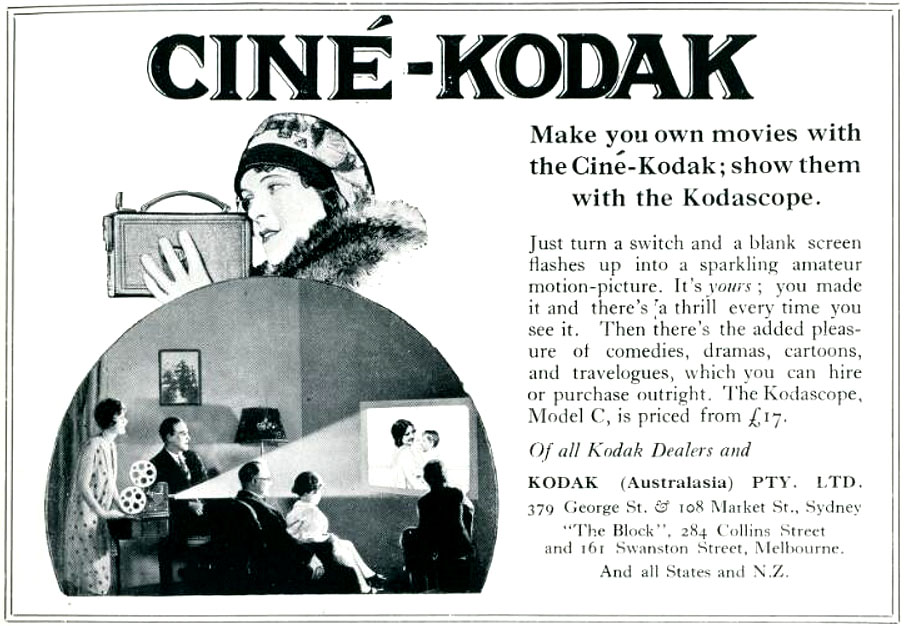

In 1923, Kodak launched 16mm reversal film for its new Kodascope projector. This would become a defining event in home video history, as it proved to be the sweet spot for non-theatrical film. Films became even more affordable, as the gauge was smaller and didn’t require a negative to print from. As a result, more projectors found their way into lodges, churches, schools and homes. The release of the format also coincided with the mass electrification of homes throughout the US and Europe, making the domestic film projector more efficient and easier to use than ever. The following year, Kodak created the Kodascope library to meet the demand of the growing home projector market - a film rental service for 16mm (and later 8mm) printed films. Wilard Cook, the primary force behind the 28mm gauge in the US, basically abandoned his format to manage the 16mm Kodascope library for Kodak. With Cook no longer at the helm of the 28mm format, it is essentially replaced and forgotten.

As the head of the Kodascope library, Cook carries over his experience with the Pathescope library to his new employer. In fact, he uses much of the same text from his Pathescope catalogs in the early Kodascope catalogs. In one such catalog from 1926, he describes their service as such:

“A Film Library is like a Book Library in that it is subject to constantly changing demands for the subjects in its possession. Unlike a Public Library, however, a Film library is a business institution, which must earn its expenses and a fair return upon the capital invested, and it is quite evident that this can only be done by keeping the films continuely in use.”

By this time, they have 14 film libraries across North America. Many of their rental policies mirror what we would see in video stores decades later, including deposits or late fees.

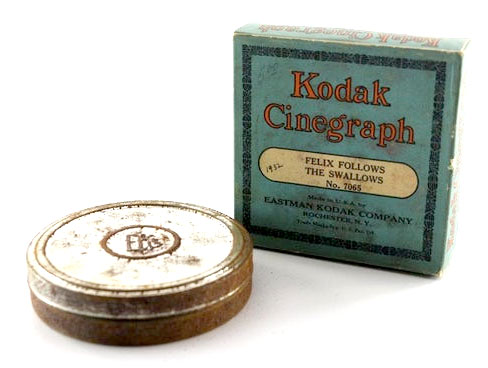

In 1927, Kodak began to market 4-minute 16mm films available for purchase, which they called Cinegraphs. According to The New York Times, “The Cinegraphs will permit individuals to start their own libraries of short pictures, much as phonograph owners collect records.” These early films include newsreels, travelogues and shorts from stars such as Charlie Chaplin and John Barrymore. Although printed films were already available, this is the first time a large push is made to create a market for home movie collecting in the U.S., as opposed to just renting them through catalogs.

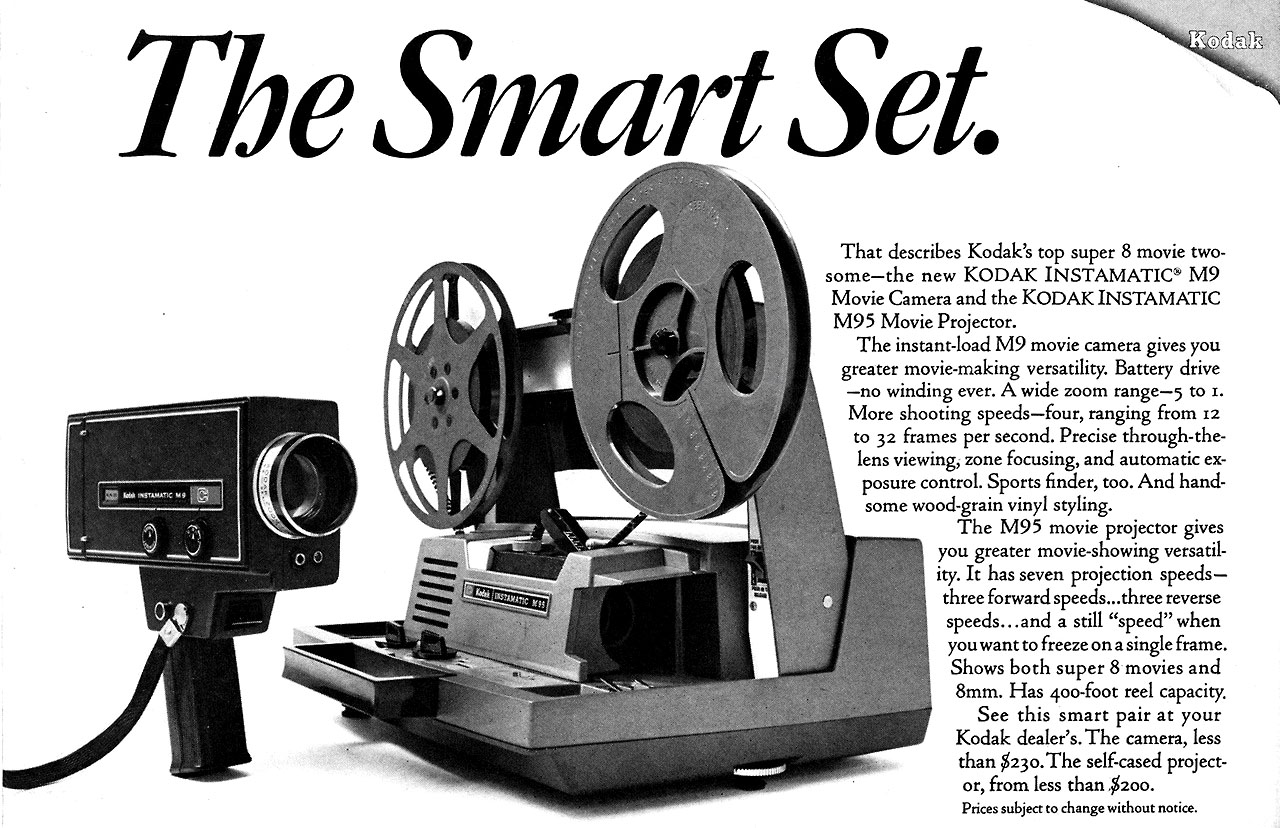

In 1932 during the Great Depression, Kodak released an even more affordable amateur film stock, the 8mm film format. Soon enough, companies who were already releasing printed 16mm films would also include 8mm versions in their catalogs as cheap alternatives. Even Pathe’s popular 9.5mm format is eventually replaced by the new format. 8mm proved to be so immensely popular that it had lasted over thirty years before it was finally given an upgrade. First released in 1965, the Super 8 format reconfigures the film, making the sprocket holes smaller to increase the frame size by 50%. In addition to this improvement, fresh reels were housed in cartridges which were easily loaded into a camera (a feature that had been forgotten since Pathescope’s 9.5mm format). An easier to load camera meant more home movies being produced, and thus, more homes having projectors. This tremendous leap forward made it the most popular motion picture home media at the time.

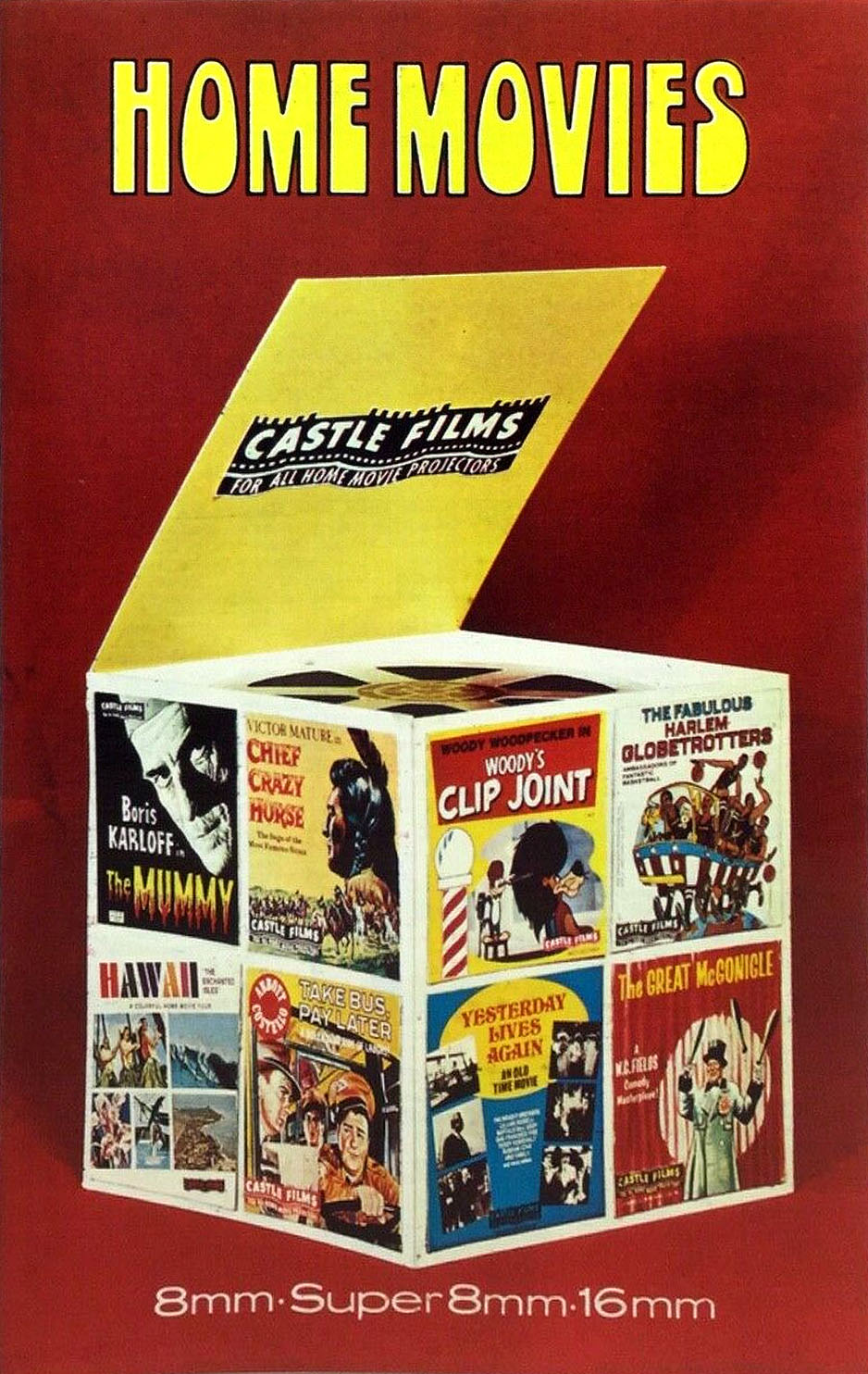

But even before Super 8 revolutionized amateur motion picture film in the 1960s, projector sales had already been soaring since the 1940s with the onset of World War II, as the American public wanted to see with their own eyes what was being described in their local newspapers. Projectors were finally recognized as a common household appliance, as proven by the many projector ads printed in the women's magazines of that day. Naturally, more and more home movie distributors began popping up, offering both licensed and public domain films in digest versions on 16mm, 8mm and later, Super 8. Among these early home movies distributors were Official Films, Ken Films and the king of them all, Castle Films. Many of the major film studios also jumped into the home movies market by either licensing their content or creating their own home movies divisions. All of which would later be replaced by, or in some cases adapt to, the coming video age in the late 1970s. Where home movies found themselves competing with television as a separate technology, videocassettes would become an extension of it.

Comments 0

Login / Register to post comments